Introduction

Since the late

Eighteenth Century, the Pyrenees, both in the

French and in the Spanish slopes, have become a centre of interest to Natural

History scholars and, at a later date, Romanticism brought them into fashion

among travellers willing to get in touch with Nature at its most rugged. Scientists

gradually dealt with their description, the measuring of their peaks’ height

and the study of the glaciers which, in spite of their southern location, remained

-and are still extant- in some Central Pyrenean areas.

In 1874, the

Bordeaux Physics and Natural Sciences Society did publish in its Annual Report

a map of an astonishing accuracy and with a graphic design of amazing quality;

an innovative work as regards the natural effect of the orographical

configuration. It had been prepared, drawn and, later on, engraved by just one

person: a young man, born in Bordeaux;

an autodidact hardly known, or even unknown, in scientific circles: Jean Daniel

François Schrader (1844-1924), better known as Franz Schrader. This geographer,

cartographer and landscape painter was also the first scholar who undertook the

study of Spanish glaciers, and we are indebted to him for the first description

thereof and the first measuring of their dimensions.

In Spanish scientific

literature, the first morphological analyses of the Spanish Pyrenees glaciers did

appear in the early nineteen-seventies, but the first overall study took place

between 1978 and 1982, and was carried out by the Spanish Glaciological

Institute (INEGLA), its main findings being published in 1988. For the

aforesaid study, the best data then available were used, including the 1956-57

flight and a specific photogrammetric flight made in 1982. In the said survey, the

inventory of glacier formations and a complete set of maps on a 1;5,000 scale,

the most detailed and accurate carried out so far, were included.

“The Maladeta Massif as seen from the Benasque, Huesca, Mountain Pass”. Painting by

Franz Schrader,

author of the

first estimate of the area covered by Spanish glaciers (1871)

These first

works were the starting point for the establishment of systematic controls

within the framework of the ERHIN programme. In this stage -which has been

continuously going on up to and including the present time- the gathering has

been achieved of direct information on the evolution of Spanish glaciers by

means of the carrying out of fieldwork, aerial photography, new photogrammetric

flights (1988) and satellite images. Besides, research has been conducted on other

French and American documentary sources, all of which has made it possible to

plot the evolution of Spanish glaciers over the last 150 years.

Current glaciers

Location of Pyrenean glaciers

The only

active glaciers currently remaining in the Iberian

Peninsula are located in the Pyrenean mountain range. In the early

Twentieth Century, they took up an area of approximately 3,300 hectares, a

figure which nowadays has been reduced to barely 400 hectares (390 hectares). Out of

this area, slightly more than half (58%) belong to the Spanish slope (206 hectares). These

glacier formations are Europe’s southernmost reserve, being located at,

approximately, the Forty-second parallel, with the exception of the Llardana

glacier, the southernmost of them all, whose position has been ascertained at a

latitude of 43º 39’

20”N.

The top

altitude of all six mountain massifs where the glaciers are located exceeds 3,000 metres, but

their different shapes, locations and orientations give rise to an irregular

distribution of the glaciated area. Thus, the Aneto-Maladeta Massif -the

largest one- has a 116-hectare area, amounting to more than half the total of Spain’s

glacier area, whereas the rest is located, almost in its entirety, in Monte

Perdido, Picos del Infierno and Posets. The massifs taking in the glaciers

belong to the catchment basins of branches of the river Ebro, the biggest in

the Peninsula (Gállego, Cinca, Ésera-Garona and

Noguera Ribargozana rivers).

In this

mountain area a total of 18 glacier formations can be found, only 9 of which

can still be deemed to be proper glaciers; the remaining nine being clearly

regressive or residual variations which can be called rocky glaciers or ice

masses.

THE ERHIN PROGRAMME

“Assessment of water resources deriving

from snowfall”

In 1981, the

Directorate General of Hydraulic Works (nowadays known as Directorate General

of Water, dependent on the Ministry of the Environment) set the ERHIN (Assessment

of Water Resources deriving from snowfall) programme in motion, whose main

purpose is the systematic control of snow reserves available at each moment in

time in the different Spanish mountain environments, so that the water

contributions resulting from the thaw of such reserves, be integrated into the

general management of water resources in the Spanish territory. This programme

included a survey of active glaciers in the Spanish Pyrenees with a view to

knowing their condition and importance.

The survey, carried

out between 1981 and 1983, made it possible to accurately set the location and

dimensions of the different glaciers, which were characterized and mapped in a

sufficiently precise detail for the time. A series of measurements were

concurrently taken in the largest glaciers (Aneto, Maladeta and Monte Perdido) and

the volume was measured of the liquid flow coming from them during the low

water-level period.

All these works did

create a solid knowledge base which has been of use at developing the current

glaciological studies of the Spanish Pyrenees, that have eventually led to the

geomorphological and glaciological interpretation of the different glaciers. These

first studies, besides, made it possible to verify the limited impact of waters

deriving from the melting of glacier ice on the hydrological system of the Ebro basin as a whole.

In its latest stage,

in addition to providing previously carried out surveys with continuity, ERHIN has been directed at reflecting possible

changes that may come about in our country, at preparing an annual record on

the state of the snow in the Spanish mountain ranges and at generating

information almost in real time on the evolution of the snow cover and the

volumes of flow coming from its thaw, with a view to achieving optimal

management of available resources.

Formation and

evolution of Pyrenean glaciers

The remotest

precedents of these current glaciers are to be found in the great quaternarian glaciations

which, throughout the Pleistocene, did affect large areas of the planet, including

diverse mountain areas in the Iberian Peninsula.

The last of such periods (Würm), did create in the Spanish slope of the

Pyrenees thick layers of ice which covered the highest areas in the mountain

range and from which large glacier tongues did issue -in some cases, up to

40-kilometre long, 3-kilometre wide and more than 600-metre thick- which

converged to the main valleys and went down to a height of 900 metres, creating

true valley glaciers, similar to the ones that nowadays can be found in the

Himalayas or in Alaska. From the last glacier maximum on -about 20,000 years

ago-, the climate became hotter and the Pyrenean ice tongues began a slow but inexorable

retreat which was only interrupted by small advances.

Already in

historical times, a climatic worsening came about known as the Small Ice Age (SIA),

a period lasting from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Centuries. During that

time many Pyrenean glaciers underwent reconstruction, indeed advancement, the

ones still existing today being the result of the said, fully historic process.

As confirmed by many of the remains, the cirques were, once again, filled with

ice and incipient tongues were formed which, in the cases of La Maladeta or

Aneto, reached a length of about 2 kilometres, 300 metres below their

current spot height. This last glacier drive came to an end in 1860, a regression starting

then which goes on into the present day.

By the end

of the Eighteenth Century, the first descriptions by travellers, scholars and

Pyrenees enthusiasts (the so called “Pyreneeists”), depicted the glaciers in a

condition that must be that of their maximal development in historical times, something

that can be nowadays be verified by the well-defined morainal structures and

other clear geomorphological traces left on the ground.

As already

stated above, the first measuring of the glaciers in the Spanish slope of the Pyrenees was carried out by the French geographer F.

Schrader between 1880 and 1894. His studies gave the overall area covered by

glaciers in the Spanish slopes an extension of 1,179 hectares. Later

on -between 1900 and 1909- Ludovic Gaurier did conduct new measurements coming

to the conclusion that the figures given by Schrader could be excessive.

|

GLACIER EVOLUTION IN THE SPANISH PYRENEES 1894-2007

|

|

|

1894

|

1982

|

1993

|

2002

|

2007

|

|

Number of glaciers

|

27

|

25

|

14

|

9

|

9

|

|

Number of

rocky glaciers

|

|

2

|

3

|

3

|

3

|

|

Number of

ice masses

|

|

4

|

14

|

6

|

6

|

|

Number of

extinct glaciers

|

|

0

|

3

|

16

|

16

|

|

Total

number of glacier formations

|

27

|

34

|

34

|

34

|

34

|

|

Total

number of massifs

|

|

10

|

10

|

6

|

6

|

|

Undefined (1982)

|

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

Total area (in

hectares)

|

1.779

|

595

|

468

|

277

|

206

|

|

Total Volume

(hm3)

|

886

|

107

|

75

|

45

|

30

|

Note. 1894

Data: Franz Schrader. 1982 Data: INEGLA. 1993-2002-2007 Data: ERHIN

One century

after the taking of the first measurements, the Spanish Pyrenean glaciers and

ice masses only covered an extension of about 600 hectares, which in

1993 had been further reduced to approximately 470 and in 2002, did not exceed 280 hectares. Finally,

according to the latest data, the area has gone on diminishing until reaching

roughly 206 hectares

(2007). So accelerated a degradation process has specially affected the smaller

glaciers, leaving them in a critical condition or bringing their extinction

about. As a result of this conspicuous regression process, some of the glaciers

described in the nineteen-eighties have clearly evolved towards a loss of mass,

thereby leaving the category of glaciers and becoming ice masses, or even

extinct.

|

EVOLUTION OF GLACIER AREAS IN THE

SPANISH PYRENEES. 1894-2007

(Evolution by the massif in terms

of hectares)

|

|

MASSIF

|

1894

|

1982

|

1993

|

2002

|

2007

|

|

Balaitus

|

55

|

18

|

13

|

0

|

0

|

|

Picos del Infierno

|

88

|

45

|

38

|

24

|

20

|

|

Viñemal

|

40

|

20

|

17

|

2

|

1

|

|

Taillón

|

|

10

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

|

Monte

Perdido

|

556

|

107

|

74

|

44

|

38

|

|

La Munia

|

40

|

12

|

8

|

0

|

0

|

|

Posets

|

216

|

59

|

52

|

39

|

25

|

|

Perdiguero

|

92

|

10

|

9

|

0

|

0

|

|

Aneto-Maladeta

|

692

|

314

|

249

|

162

|

116

|

|

Besiberri

|

-

|

-

|

6

|

6

|

6

|

|

TOTAL FOR THE PYRENEES

(hectares)

|

1.779

|

595

|

468

|

277

|

206

|

Nota. 1894

Data: F. Schrader’s estimate; 1982: INEGLA; 1993-2002-2007: ERHIN

In this

process, reductions as well as increases can, accordingly, be observed, which

were caused by the disintegration of a large glacier into one or two formations.

Nowadays, there only remain 18 out of the 34 described in 1982, as can be seen

in the table below. Out of the surviving number, nine are proper glaciers,

three are rocky glaciers and six are ice masses.

South-facing

slopes, whose glaciers were initially less developed and in fragile

morpho-climatic conditions, have undergone the total loss of ice, with the

exception of the Aneto’s southern slope where the small “Corona” ice mass still exists. This has resulted

in the border massifs of Balaitus, Taillón, La Munia and Perdiguero, whose

north-facing slopes are entirely in French territory, ceasing to count as

Spanish glaciated areas. In all remaining cases, a significant backward

movement has been detected which, in general, can be deemed to be serious with

marked losses of volume, area and length, along with a shortening of the

altitudinal ranges of occupancy by the ice.

Variation in length of glaciers in the Spanish Pirineo

Climatic

change and glaciarism

The glacier regression stage which can currently be

noticed in the Pyrenees is in keeping with what, generally speaking, is being

pointed out throughout the world, and which seems to have a connection with the

establishment of a warm climatic trend and with a certain change in the

precipitations regime. Regardless of the knowledge or otherwise of the ultimate

causes being responsible for the degradation process, it seems obvious that,

unless the current regressive trend affecting all our glaciers be changed, the

Twenty-first century can witness -perhaps within a few decades-, the complete

or nearly complete extinction of the last ice reserves in the Spanish Pyrenees

and, therefore, an important change in the current mountain landscape.

Map of Monte Perdido, in the Central Pyrenees. Bourdeux, 1874

1.

Balaitús

The Balaitús

is a granitic massif located at the Spanish-French border, whose height reaches

3,144 metres.

In this massif, studies have been carried out of the Small Ice Age (SAI)

glacier marks. A glacier and two ice masses can currently be seen in the massif:

the former is called Las Néous (subdivided into two masses) and the first ice

mass is known as Pabat (both being located in France);

the Frondillas Norte ice mass is located in Spain. It can be asserted that they

are residual formations in a highly advanced extinction process, save for the Las

Néous glacier, thanks to its being located in the shady mountainside and to the

snow contributions coming from the Northern-Pyrenean slope.

2. Picos del Infierno

This massif

is named after the highest peaks of the range as a whole, but its naming is

extended to include an area encompassing different peaks and glaciers. The

waters of this massif finally drain into the river Gállego through several

sub-tributaries. Glacier formations include the rocky glacier of Las Argualas, which

is the largest in the group. Schrader, in his 1894 observations, located one

single glacier in the western Pico del Infierno and did not count the Punta

Zarra ice mass, estimating the total area at 88 hectares. In 2007, in the massif as a

whole there remained only the Picos del Infierno glaciers (western and eastern,

although the latter is reduced to an ice mass), the Las Argualas rocky glacier

and the Punta Zarra ice mass, jointly covering an area of 20 hectares.

3. Viñemal

Standing 3,299 meters high, the

Viñemal peak is the loftiest in the French Pyrenees. It is located between France and Spain,

specifically, in the province

of Huesca, within the

boundaries of the Ordesa y Monte Perdido National Park, at the upper end of the

Ara river valley. This massif consists of ten mountains arranged in the shape

of a crown, all of which exceed 3,000 metres. In it, several glacier formations

are located: Ossue, Gaube, Montserrat and Clot

de la Hount, among others. There is abundant information about the retreat

undergone by the first two: at the end of the Eighteenth Century, the Ossue

glacier was 3-kilometer long. Nowadays there remain three glacier formations

two of which are of a very small size (Petit Vignemale and Oulettes) plus a

third (Ossue) which covers an area of 59 hectares, in

addition to three ice masses.

4. Taillón

Taillón is a

peak of an altitude of 3,144

metres located at the Spanish-French border. It is a

part of the northern end of the Ordesa y Monte Perdido National Park. The

evolution undergone by this glacier is as follows: in 1982 it was classified as

a glacier, covering a 10-hectare area and being 415-metre long. In 1993 joined

the ranks of the ice masses, upon experiencing a 80% reduction in area, and a 40%

one in length. In 2002 has been classified as “extinct”.

5. Monte Perdido

Ordesa y Monte Perdido National Park. Source: MARM, National Parks Autonomous Authority

The Monte

Perdido massif is one of the most spectacular and best known in the Pyrenees, due to the stunning beauty of its morphology, and

is located at the upper end of two highly representative valleys of the

mountain range: Ordesa and Pineda. The summit after which it is named reaches 3,355 metres. The

glaciated area is the second largest in the Pyrenees,

after the Aneto-Maladeta massif, even though it is currently much diminished. In

1894 the Pyreneeists Schrader counted five glaciers and estimated its area at 556 hectares. In the

1980 observations, the extinction was already verified of three of them, as

well as the division of the main glacier into four. The area estimated at that

particular date amounted to just 107 hectares. According to the 2007

observations, this massif is in a critical condition, for there remain just two

real glaciers: Upper and Lower Monte Perdido plus a residual ice mass. The

total glaciated area covers 38

hectares.

6. La Munia

This massif

reaches a height of 3,134

metres. Almost seven cirques are located in it, whose

shapes are attributable to the Small Ice Age and which have undergone a

degradation process since the Nineteenth Century. The most important remains

are to be found in the cirques located in the shady slope and facing north,

with glaciers, which at certain moment in time reached low spot heights (2,370 metres in Barroude),

being abundantly overfed by avalanches. The Robiñera ice mass did evolve until

it became extinct (1982-1993), going, in little more than ten years, from an

extension of 12 hectares

to just 8; and from 525 to 300

metres in length. From 1993 onwards the regression

started until total extinction was achieved in 2002, a situation that

remains in 2007.

7. Posets

The Posets

massif belongs with its namesake peak (3,375 metres), the

second highest in the Pyrenees. It is made up

of different glacier formations whose extension and nature have gradually

changed as time went by, and in a far more pronounced way over the last few

decades. In 1894 Schrader described four formations in this massif, all of

which were classified as glaciers: Llardana, Posets, Los Gemelos and Espadas, which,

as a whole, did cover a glaciated area with an extension of 216 hectares. In the

1980 observations, the extinction was verified of the Espadas glacier, as was

the division of that of Posets into two formations, there remaining an ice area

of just 59 hectares.

The Los Gemelos glacier was then classified as a rocky glacier. After the

aforementioned date, the Posets glacier has joined the “ice mass” category, its

extension having been reduced to 25 hectares (2007).

8. Perdiguero

It is a

granitic massif located between the Aragón and the Upper

Garonne river basins, comprising numerous peaks whose altitude

exceeds 3,000 metres,

the highest mountain reaching 3,221 metres. It includes 16 cirques. The

preservation of abundant remains dating back to the Small Ice Age is due to the

northerly orientation, the high altitude and the uninterrupted walls of the

cirques. The glacier known as Literota had in 1982 an extension of 10 hectares and was

450-metre long; in 1993, following a 60% reduction in extension and length,

which happened just over an 11-year period, it became an ice mass, being

declared extinct in 2002. As regards the Remuñe glacier, no data were available

in 2002, but those for 1993 made it possible to classify it as an ice mass, with

a 5-hectare extension and being 120-metre long. In 2002 it was already declared

extinct.

9. Aneto-Maladeta

Rolando's Breach. Source: MARM, National Parks Autonomous Authority

The Aneto-Maladeta massif is

undoubtedly the best known and the most representative in the whole of the

Pyrenees, as a result of both including the highest peak in the mountain range (Aneto,

3,404 metres),

and the extension and the -relatively- good state of preservation of its

glaciers, due not only to its altitude, but also to its massiveness and

northerly orientation. The massif is located at the upper end of the Benasque

valley, a typical example of sink-shaped glacier valley, through which the

Esera river waters run. In spite of being the most important massif, the effect

of regression is also remarkable here, as shown by the figures accounting for

the loss of glaciated area

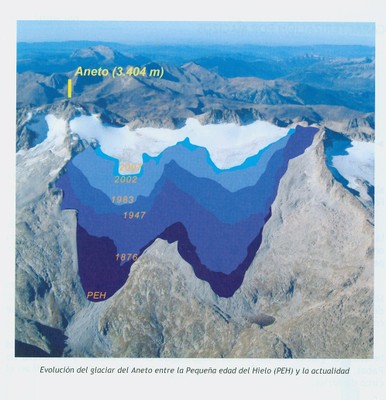

Evolution of Glacier Aneto between the Little Ice Age (PEH) and the present

In 1894

Schrader counted a total of 10 glaciers covering a 692-hectare area. The 1980

observations verified that the number of formations remained unchanged, but the

glacier area was estimated at 314 hectares. Between 1990 and 2007 the

situation dramatically changed: the La Maladeta glacier was divided into two (1992); the

Coronas glacier has been turned into an ice mass, while the old glaciers of Cregüeña

(1998) and Llosás (1994), Salencas and Alba have disappeared. The glacier

extension estimated in 2007 amounts to just 116 hectares.

10. Besiberri

It has four

peaks more than 3,000-metre high, the highest one reaching 3,024 metres. It is

located in the Upper Ribagorza district, at the boundary of the Aigües Tortes y

Estany de Sant Maurici National Park.

From a geomorphological standpoint, it is characterized by the presence of

moraines and a rocky glacier belonging to the cirques made up of the main

summit line and the adjacent crests. In 1982 it did not have any specific

category and in 1993 it was classified as a rocky glacier, covering a 6-hectare

area and being 735-metre long, a situation which remained until 2007.

LEGAL PROTECTION OF SPANISH GLACIERS

The Spanish

Pyrenean glaciers are protected, either directly or indirectly, by legislation both

national and regional in scope. Conservation policy in Spain is

currently governed by Act 42/2007, promulgated on December 13, on Natural

Heritage and Biodiversity, article 33 of which mentions “natural monuments”,

a category which includes glaciers. Some of the most important are located

within the Ordesa y Monte Perdido National Park.

It is worth

remembering that Spain was one of the countries that pioneered the protection

of natural areas, backing the late Nineteenth-century conservationist school

thanks to the initiative of Pedro Pidal Bernardo de Quirós, who succeeded in

having the December 7, 1916, National Park Act promulgated, for the

purpose of “respecting the natural beauty of their landscapes, the richness of

their fauna and flora, as well as the special hydrological and geological

features they may contain, and causing them to be respected, preventing in this

manner and with the highest efficiency, every act of destruction, defilement or

disfiguration by man”.

As we have

briefly stated, the Spanish Pyrenean glaciers are undergoing a marked retreat

in terms of area covered and volume, due to the conjunction of climatological

changes -such as the increase in temperature and the decrease in winter

precipitations- which have led the different glacier formations to the

condition they are in today. Only a universal fight against climate change

could alleviate this situation.

A) Pyrenean glaciers’ Natural Monuments. The glaciers

of Balaitús, Picos del Infierno, Vignemale, La Munia, Posets, Perdiguero and

Aneto-Maladeta are protected by Act 2/1990, promulgated on March, 21 by

the Aragon Regional Parliament. The said protection includes the glaciers

proper and their morphological environment, encompassing the geology, the

fauna, the vegetation, the water and the atmosphere. Act 2/1990 gives emphasis to their high

scientific, cultural and landscape-related interest, whereby, in accordance

with the regulations, outlying protection areas will be established aimed at preventing

landscape-related or ecological impacts, thus averting any action entailing the

destruction, the defilement, the transformation or the disfiguration of the

glaciers’ features and their natural evolution processes.

B) Ordesa y

Monte Perdido National Park. All the described glaciers are located in the province of Huesca, and the most important glacier

formation is to be found in this National Park which, nowadays, has an

extension of 15,608

hectares, as a result of successive enlargements. It was

declared a National Park (under the name of Valle de Ordesa National Park) at a

very early date, thus becoming one of the world’s first protected areas (Royal

Decree passed on August, 16, 1918). It was reclassified, under its current

name, by Act 52/1982 promulgated on July 13.

Royal Decree

409/95 approved its Use and Management Ruling Plan (PRUG). It is also affected

by Act 8/2004, promulgated on December 20, on Urgent Measures in matters

pertaining to the Environment, and by Decree 117/2005, promulgated on May 24 by

the Aragon Regional Government, whereby the organization and operation is

regulated of the Ordesa y Monte Perdido National Park. Since July 1, 2006, the

National Park’s management is the Self-governing Aragonese Region’s exclusive

responsibility. The transfer of functions and services to this Self-governing

Region by the Central Government was made under Royal Decree 778/2006, passed

on June, 23, and the broadening of human and financial resources took place

under Royal Decree 446/2007, passed on April 3.

The Ordesa y

Monte Perdido

National Park is included in the Ordesa-Viñamala

Reserve of the Biosphere, it being the first (1977) of the Reserve

proposals submitted in Spain.

The Reserve covers an area almost three times larger than the Park (51,396 hectares), including

nine municipalities and about 6,000 inhabitants. The Reserve is an exceptional

sample of the phenomenon of glaciarism which has sculpted the orography,

creating deep U-shaped valleys, cirques and lakes excavated by ice (locally know

as “ibones”). The flora diversity includes more than 2,000 inventoried species.

It must also be pointed out that in 1977 it was designated a UNESCO World

Heritage Site. Since 1988 a

Special Zone for the Protection of

Birds (ZEPA) is located within its confines, and it is a

member of the Natura 2000 Network.

C) Posets-Maladeta

Natural Park. It has an extension

of 33,267 hectares.

It was declared a Natural

Park under Act 3/1994,

promulgated on June 23, by the Aragon Regional Parliament. In the preamble

of the said Act, it is remembered that “The Posets and Maladeta massifs, in the

Aragonese Pyrenees, are two of the largest Spanish mountain nuclei. Among its

peaks, the two highest in the whole of the Pyrenean mountain range are to be

found: Posets, standing 3,375

metres high, and Aneto, in the Maladeta massif, reaching

an altitude of 3,404

metres. The whole made up of its large glaciers, crests

and peaks (there are more than 30 exceeding 3,000 metres in height),

large wooded valleys, the high number of “ibones” and lakes of outstanding

beauty, and gorges, constitute an extraordinarily valuable ecosystem”.

Main Sources:

- Arenillas,

M.; Cobos, G.; Navarro, J. [Estrela, T.; Francés, Miguel, coord.] : Datos

sobre la nieve y los glaciares en las cordilleras españolas: el programa ERHIN

(1984-2008). Madrid: Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, y Medio Rural y Marino,

Dirección General del Agua, 2008.

- Fundación

para la Investigación

y el Desarrollo Ambiental (FIDA): Las Reservas de la Biosfera en España: el Programa MaB de la UNESCO.[Madrid], 2002

- Martínez de

Pisón, E.; Arenillas, M.: Los glaciares actuales del Pirineo español, in La nieve en el

Pirineo español, pág. 29-98. Madrid:

Ministerio de Obras Públicas, 1988

- Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, Centro

de Publicaciones: La nieve en las cordilleras españolas [periodical

publication] 1 CD-ROM. Contents: Volume I: 1995-1996 to

1997-1998. Volume II: 1998-1999 to 1999-2000. Volume III: 2000-2001 to

2002-2003

- Ministerio

de Medio Ambiente, y Medio Rural y Marino. Organismo Autónomo de Parques

Nacionales. Ier Informe de situación, a 1 de enero de

2007, de la Red

de Parques Nacionales, Madrid, abril 2008 [Report submitted to the Senate] http://reddeparquesnacionales.mma.es/parques/org_auto/informacion_general/red_informe.htm

- Saule-Sorbe,

Hélène: En torno a algunas orografías realizadas por

Franz Schrader en los Pirineos españoles , in ERIA, Revista

cuatrimestral de Geografía: nº 64-65, 2004, p. 207-220 (Issue devoted to the

History of Spanish Cartography)

- National

Parks Website: Parque

Nacional de Ordesa y Monte Perdido. http://reddeparquesnacionales.mma.es/parques/ordesa/index.htm

Document Actions

Share with others