Every day, we are surrounded by hundreds or thousands of synthetic chemicals. They are in our food, clothes, tools, furniture, toys, cosmetics and medicines. Our society would not be the same without these substances. However, despite their usefulness, we know many of these substances can have negative impacts on our health and the environment.

According to some estimates, about 6 % of the world’s disease burden — including chronic diseases, cancers, neurological and developmental disorders — and 8 % of deaths can be attributed to chemicals. Moreover, these numbers could be growing and they take into consideration only a small number of chemicals whose effect on health is well established.

Dangerous cocktails and ‘forever chemicals’

More than 300 million tonnes of chemicals were consumed in the EU in 2018 and more than two thirds of this amount were chemicals that are classified as hazardous to health, according to Eurostat. Over 20 000 individual chemicals have been registered in the EU under the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) Regulation.

As these numbers keep growing, it is increasingly difficult to assess all the effects that chemicals have on our health and the environment case by case. Most studies so far have investigated the effects of only single chemicals and their safe thresholds but people are constantly exposed to a mixture of chemicals. This combined exposure can lead to health effects, even if single substances in the mixture do not exceed safe levels.

Moreover, persistent chemicals can accumulate in human tissues, causing negative health effects after long‑term exposure. For example, per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS) are a group of almost 5 000 widely used chemicals that can accumulate over time in humans and in the environment. They are an example of persistent organic pollutants — the so-called forever chemicals.

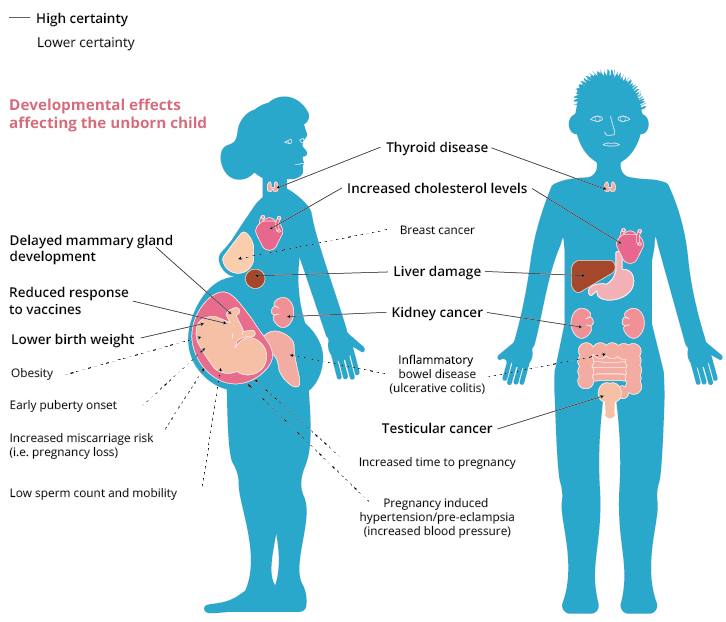

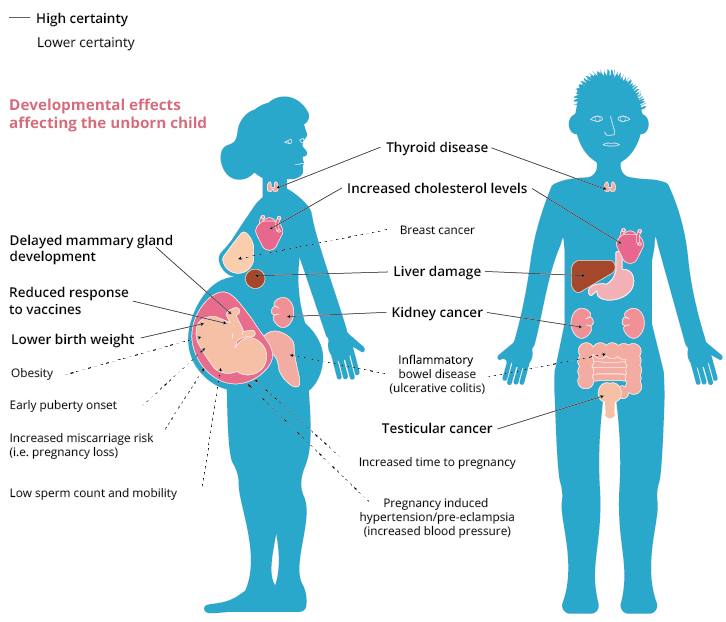

People are mainly exposed to PFAS through drinking water, food and food packaging, dust, cosmetics, PFAS-coated textiles and other consumer products. The effects of human exposure to PFAS include kidney cancer, testicular cancer, thyroid disease, liver damage and a series of developmental effects affecting fetuses.

Using PFAS-free products and cooking materials helps to reduce exposure. General and specific guidance on how to find PFAS-free alternatives is often provided by consumer organisations and national institutions working on the environment, health or chemicals.

The precautionary principle

The ‘precautionary principle’ could be translated into everyday words as ‘better safe than sorry’. It means that, when scientific evidence about something is uncertain, and there are reasonable grounds for concern about harm, decision-makers should err on the side of caution and avoid risks. With chemicals, the development of new substances outpaces research on their negative impacts. This is why it is important to proceed with caution.

Read more about the precautionary principle:

Communication from the Commission on the precautionary principle.

EEA’s Late lessons from early warnings II.

Effects of PFAS on human health

Per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS) are a group of extremely persistent chemicals that are used in many consumer products. PFAS are used in products because they can, for example, increase oil and water repellence or resist high temperatures. Currently, there are more than 4 700 different PFAS that accumulate in people and the environment.

Sources: US National Toxicology Program (2016); C8 Health Project Reports (2012); WHO IARC (2017); Barry et al. (2013); Fenton et al. (2009); and White et al. (2011) apud Emerging chemical risks in Europe — ‘PFAS’; EEA Infographic.

Endocrine disruptors

Some chemicals interfere with the functioning of the body’s hormone system. Exposure to these so-called endocrine disruptors can cause a wide variety of health problems, ranging from developmental disorders, obesity and diabetes to infertility in men and mortality associated with reduced testosterone levels. Fetuses, small children and teenagers are especially vulnerable to endocrine disruptors.

Approximately 800 substances are known or suspected to be endocrine disruptors and many of them are present in everyday products, such as metal food cans,

plastics, pesticides, food and cosmetics.

Endocrine disruptors include bisphenol A (BPA), dioxins, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and certain types of phthalates. Phthalates, for example, are used to soften plastic for use in a wide range of consumer goods, such as vinyl flooring, adhesives, detergents, air fresheners, lubricating oils, food packaging, clothing, personal care products and toys.

Consuming food and drinks from containers that include phthalates is one way to become exposed. Inhaling indoor dust contaminated with phthalates that are released from plastic products or polyvinyl chloride (PVC) furnishings is another. (This is one of the reasons why airing our rooms regularly is important.) Children playing with toys that contain these substances are also at risk and, since phthalates can also be found in consumer products, such as soaps and suntan lotions, exposure can also occur through the skin.

The EU has put in place measures to reduce people’s exposure to phthalates by banning the use of some of these substances and restricting the use of others in toys, cosmetics and food containers. However, older products and furnishings may contain phthalates that are now banned, so they are still present in our everyday environment.

Moreover, a recent inspection project by the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) showed that products imported from non‑EU countries can still contain phthalates. China has in recent years put in place restrictions on certain phthalates in toys and food contact materials but restricted phthalates are still found in many products imported to the EU from China and other, sometimes unknown, origins.

Concerted efforts have reduced the presence of persistent organic pollutants, such as dioxins, PCBs and atrazine, in Europe’s environment since the 1970s, but their persistence and the fact that they accumulate in the food chain, notably in animal fat, continues to cause concerns. Another concern is that some substances have been substituted for other, equally toxic chemicals.

The chemicals we eat

Pesticides are another group of chemicals that can harm our health, mostly as a result of the consumption of vegetables and fruit that have been in contact with them. Children are especially vulnerable, partly because they eat proportionally more food per kilogram of body weight than adults do. Eating organic produce can decrease this pesticide burden but not everyone can afford that.

The EU regulates pesticides under the Regulation on Plant Protection Products and sets safe limits for pesticide residues in food and feed. The latest information from the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) shows that 95.5 % of food samples collected across the EU in 2018 were within legal limits. Table grapes and bell peppers were among the food products that most frequently exceeded the legal levels of residue. Still, based on the samples analysed, containing both regular and organic produce, the probability of European citizens being exposed to dangerous levels of pesticide residue is considered low.

Not all chemical substances harmful to our health are new. For example, mercury is naturally present in the environment and has been released in air and water by human activity for centuries. However, today we know that ingesting mercury can affect the nervous system, kidneys and lungs, and exposure during pregnancy can affect the development of the fetus.

People are exposed to mercury mainly through eating large predatory fish, such as tuna, shark, swordfish, pike, zander, eel and marlin. This also means that exposure can be limited by dietary choices, which is important especially for vulnerable groups, such as expectant mothers and young children.

For a more complete picture of human exposure to chemicals, there is a need for data on what is in our bodies. This includes chemicals that we eat as well as those that enter through other exposure pathways. These types of human biomonitoring data can be used to improve chemical risk assessments by providing information on actual human exposure through multiple exposure pathways.

Human biomonitoring — measuring our exposure to chemicals

Human biomonitoring measures people’s exposure to chemicals by analysing the substances themselves, their metabolites or markers of subsequent health effects in urine, blood, hair or tissue. Information on human exposure can be linked to data on sources and epidemiological surveys, in order to inform research on the exposure‑response relationships in humans.

The European human biomonitoring initiative, HBM4EU, launched in 2017 and co‑funded under Horizon 2020, is a joint effort of 30 countries, the EEAand the European Commission.

The main aim of the initiative is to coordinate and advance human biomonitoring in Europe. HBM4EU will provide better evidence of the actual exposure of citizens to chemicals and the possible health effects to support policymaking. The project has also set up focus groups to understand EU citizen’s perspectives on chemical exposure and human biomonitoring.

Under HBM4EU, efforts are under way to generate robust and coherent data sets on the exposure of the European population to chemicals of concern. This includes producing exposure data on 16 substance groups, mixtures of chemicals and emerging chemicals, as well as exploring exposure pathways and linking exposure to health effects.

Visit: www.hbm4eu.eu

Towards a safer chemical environment

The EU has the strictest and most advanced rules in the world when it comes to chemicals. The REACH Regulation is the key piece of legislation that aims to protect human health and the environment, and the EU has put in place rules for the classification, labelling and packaging of chemicals.

Chemical effects on nature

Synthetic chemicals released into nature can affect plants and animals. For example, neonicotinoids are a type of insecticide used in agriculture to control pests that pose risks to bees, as bees are important pollinators supporting food production. Pesticides can also affect fish and bird populations and entire food chains. In 2013, the European Commission severely restricted the use of plant protection products and treated seeds containing certain neonicotinoids to protect honeybees.

The EU has a body of legislation to regulate chemicals in detergents, biocides, plant protection products and pharmaceuticals. Policies limit the use of hazardous chemicals in personal care products, cosmetics, textiles, electronic equipment and food contact materials. Limits are also in place for chemicals in the air, food and drinking water. Legislation addresses point source emissions from industrial installations and from urban waste water treatment plants.

Still, there is room for improvement to create a less toxic environment, and the European Green Deal aims to further protect citizens against dangerous chemicals with a new chemicals strategy and by moving the EU towards the zero pollution ambition.

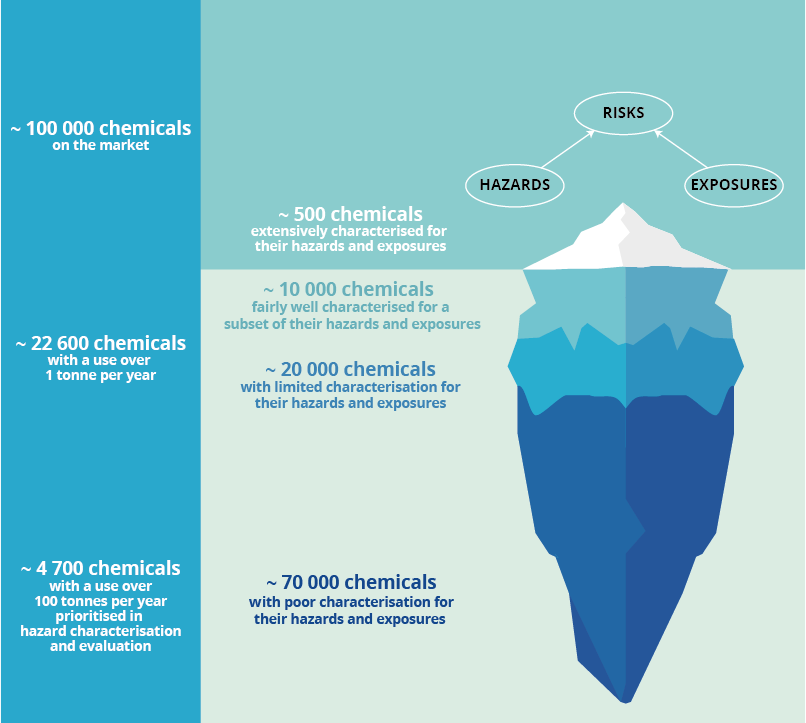

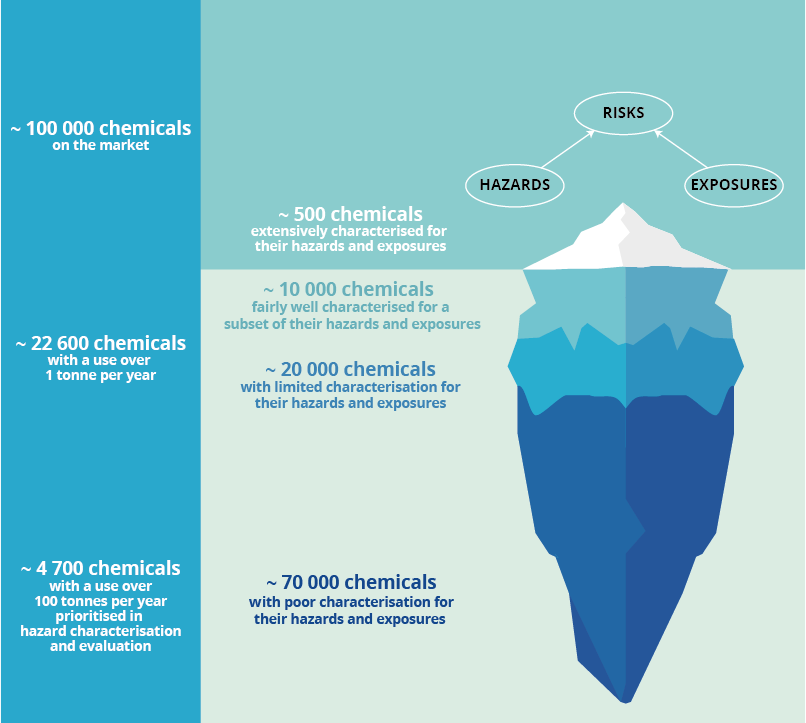

The unknown territory of chemical risks

There are many chemicals on the market and only a small fraction of these have been extensively studied for their risks. Designing safe products with a smaller number of different chemicals is one way of reducing potential risks.

Source: EEA report - The European environment — state and outlook 2020: EEA Infographic.

Document Actions

Share with others